Introduction to M&A Transaction Structure

The determination of an optimal M&A transaction structure is a complex process driven by a number of considerations.* A thorough examination of the subject could fill a book. That said, below is a brief overview of the most common transaction structures—stock purchase, asset purchase, negotiated merger and two-step merger—along with some advantages and disadvantages of each.

* Considerations include the parties’ relative bargaining power, operational needs, plans for post-closing integration, tax efficiency, accounting consequences, regulatory requirements, state corporation and alternative entity (e.g., LLC) law, foreign law, fiduciary duties, third party consent requirements, antitrust concerns, time sensitivity, diffusion of the shareholder base, shareholder approval requirements, financing needs, the nature of the consideration (e.g., whether there is an earnout or stock consideration) and more.

Structure No. 1 — Stock Purchase.

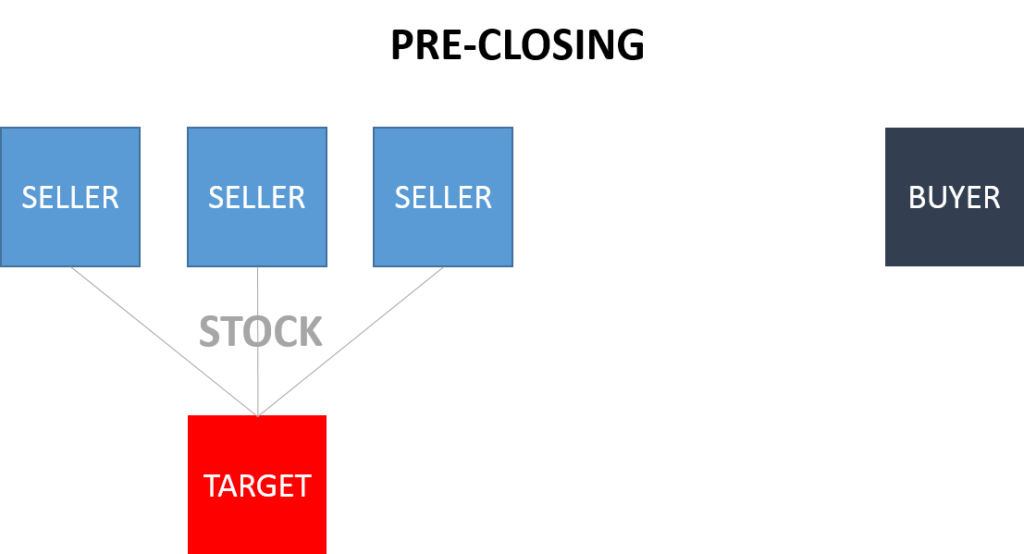

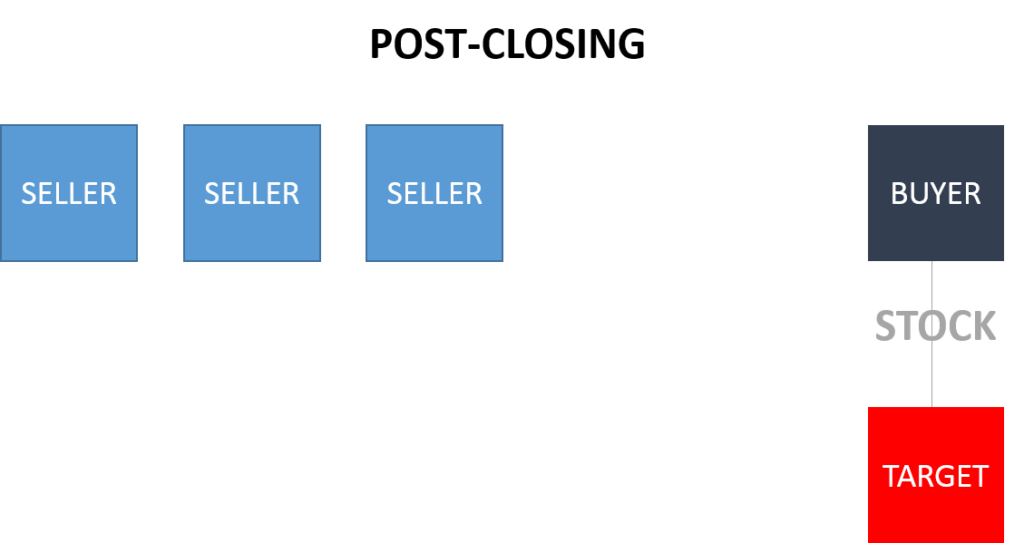

A stock purchase transaction involves the acquisition by the buyer or its subsidiary of the outstanding capital stock (or other ownership interests) of the target company. The target company itself may not need to be a party to the transaction agreements, as its ownership is changing hands, which doesn’t require any action on its part. Instead, the seller or sellers of the stock provide representations and warranties about the stock and the target company, agree to take certain actions or to cause the target company to take certain actions prior to closing and to provide post-closing indemnification.

Here’s an illustration of the stock purchase transaction structure:

The advantages and disadvantages of a stock purchase structure include, among others:

- It’s a relatively quick and simple way to consummate a transaction, as it generally requires fewer third party consents and instruments of transfer than an asset sale.

- It requires each individual stockholder selling shares to sign the stock purchase agreement or otherwise agree to transfer ownership and, usually, to provide indemnity.

- Where there are a large number of selling shareholders, stock purchase transactions become impracticable because it becomes difficult for buyers to acquire enough shares to effect a squeeze-out merger under applicable state law (e.g., §253 of the Delaware General Corporation Law) and take ownership of 100% of the target company.

- If fewer than all target shareholders are prepared to sign the purchase agreement, either the selling shareholders must provide 100% of the indemnity to the buyer or the buyer must be prepared to accept less than 100% indemnification for certain losses.

- It generally cannot be employed in public company transactions because of the diffusion of the target company’s shareholder base.

- Aside from express indemnification obligations (or exceptions to the exclusive remedy provision of a purchase agreement), selling shareholders do not retain any liabilities of the target company post-closing.

- It is generally advantageous for a seller because of the benefit from capital gains tax rates. The purchase price minus the shareholders’ basis in the stock equals the recognized gain. This gain is considered a capital gain and is taxed at the capital gains tax rate, which is usually lower than the ordinary tax rate.

Structure No. 2 — Asset Purchase.

An asset purchase transaction involves the acquisition by the buyer or its subsidiary of all or a portion of the assets and liabilities of the seller group. Unlike in a stock purchase, ownership of securities is not conveyed. Instead, assets and related liabilities of seller entities, which typically collectively comprise a standalone business or operating division of the seller group, are transferred through several instruments of transfer, including bills of sale, assignment and assumption agreements, intellectual property assignments and the like. Assets that may be sold include:

- tangible personal property,

- machinery, equipment and fixtures,

- inventory,

- owned and leased real estate,

- contract rights,

- accounts receivable,

- permits,

- books and records,

- insurance policies and related rights,

- rights to bring lawsuits,

- rights to tax refunds,

- cash,

- intellectual property and R&D and

- rights to employee personnel.

Along with these assets, buyers typically assume responsibility for specified liabilities relating to the acquired assets, which may include some combination of the following:

- liabilities reserved or accrued on the balance sheet for the acquired business,

- liabilities for taxes,

- liabilities arising under assumed contracts,

- employment and benefits liabilities,

- liabilities associated with acquired real estate,

- environmental liabilities and

- other liabilities of the acquired business arising before or after closing.

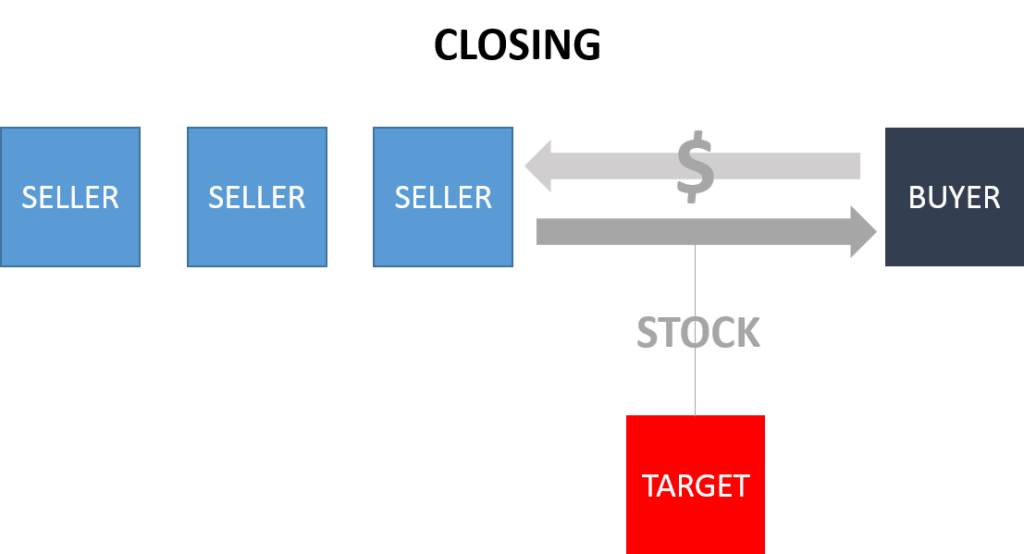

These assets and liabilities may be sold by one or more affiliated entities, depending on the organizational structure of the seller group. The seller entities, or the ultimate parent of the seller entities, will be responsible for post-closing indemnification of the buyer.

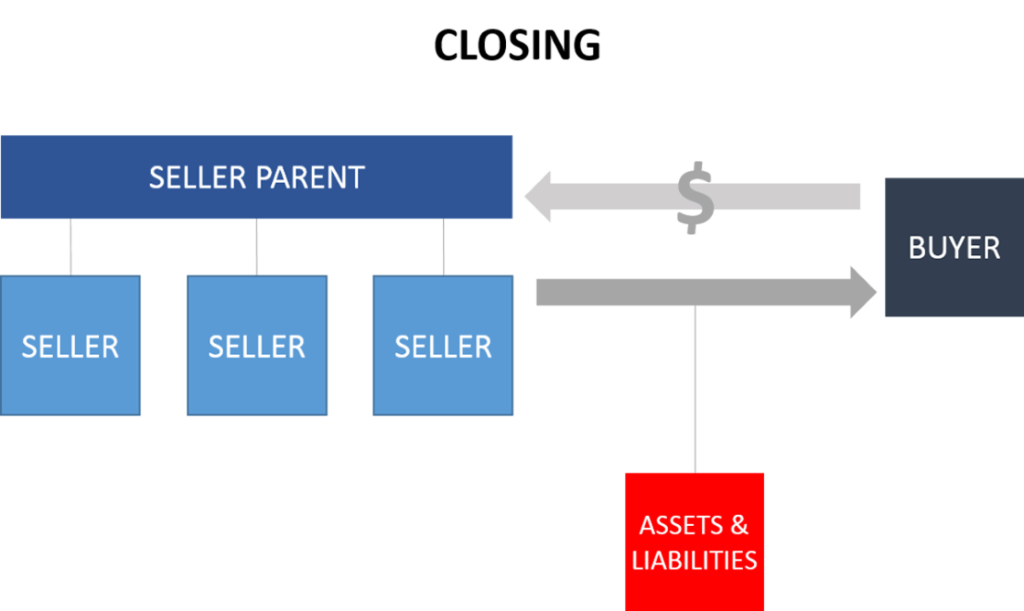

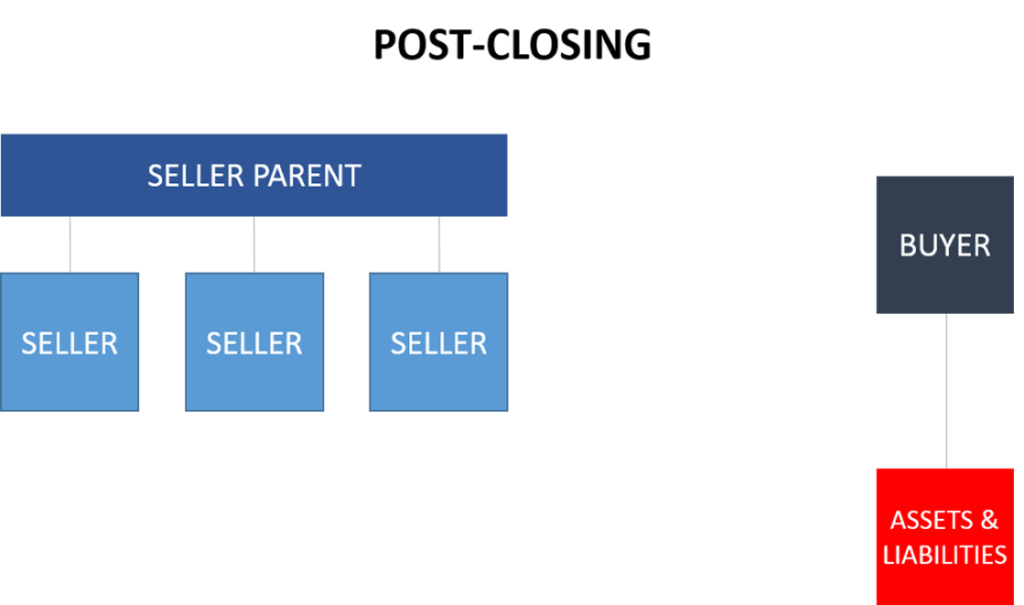

Here’s an illustration of the asset purchase transaction structure assuming multiple subsidiary sellers and a buyer not using a subsidiary structure to make the acquisition:

The advantages and disadvantages of an asset purchase structure include, among others:

- It can generally be consummated without 100% selling shareholder consent. If all or substantially all of the seller’s assets are being sold, usually holders of at least 50% of the seller’s outstanding ownership interests must approve the transaction. If less than that percentage of the seller’s assets are being sold, than no shareholder approval will be required.

- Buyer’s can be selective in choosing which assets and liabilities it wishes to accept and assume. In a stock purchase, all assets and liabilities of the acquired business transfer automatically with the stock, unless specifically excluded and transferred out of the target company. In contrast, subject to limited exceptions, a buyer only takes the liabilities from the seller in an asset transaction that it expressly agrees to accept.

- Unless the seller will be dissolved, the seller (as opposed to its shareholders) will typically bear responsibility for 100% of the post-closing indemnification obligations to the buyer.

- It may require significant and difficult to obtain third party consents to transfer the acquired assets and liabilities because direct assignments to third parties are typically subject to greater contractual restrictions than changes of control impacting a party to a contract.

- Some assets may be used by the business being sold and by the retained business of the seller, which makes it difficult to extract the acquired assets and sell a self-sufficient enterprise capable of independent operation.

- There are potentially two layers of tax applicable to the seller: (1) a corporate layer, where the seller recognizes taxable gain or loss on the sale of the assets, and (2) a shareholder layer, in which shareholders of the seller recognize gain taxed as ordinary income if the target liquidates in an amount equal to the after-tax liquidating dividend less the shareholders’ basis in the stock.

- The target’s tax attributes, such as non-operating losses (NOLs), may be used immediately to offset the target’s taxable gain. Any remaining tax attributes are lost if the target liquidates.

- The buyer assumes a stepped-up cost basis in the target’s net assets. It is consequently generally a more favorable structure from a buyer’s tax perspective than a stock sale.

Sales of all or substantially all of the assets and liabilities of a public company are usually impracticable because, among other reasons, it is difficult to distribute the entire purchase price to the target company’s shareholders due to a requirement to make adequate provision (i.e., set aside money) for contingent and future claims.

Structure No. 3 — Negotiated Merger.

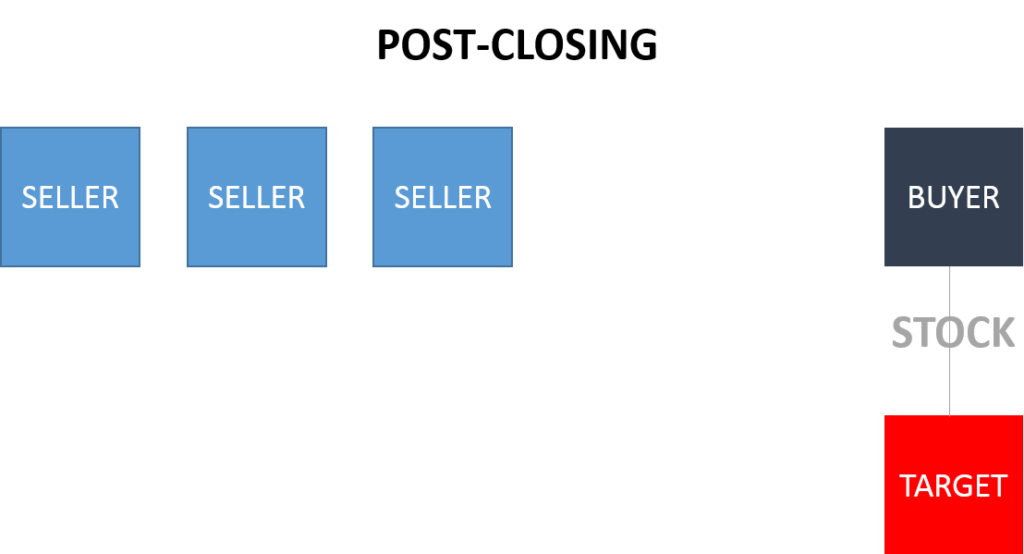

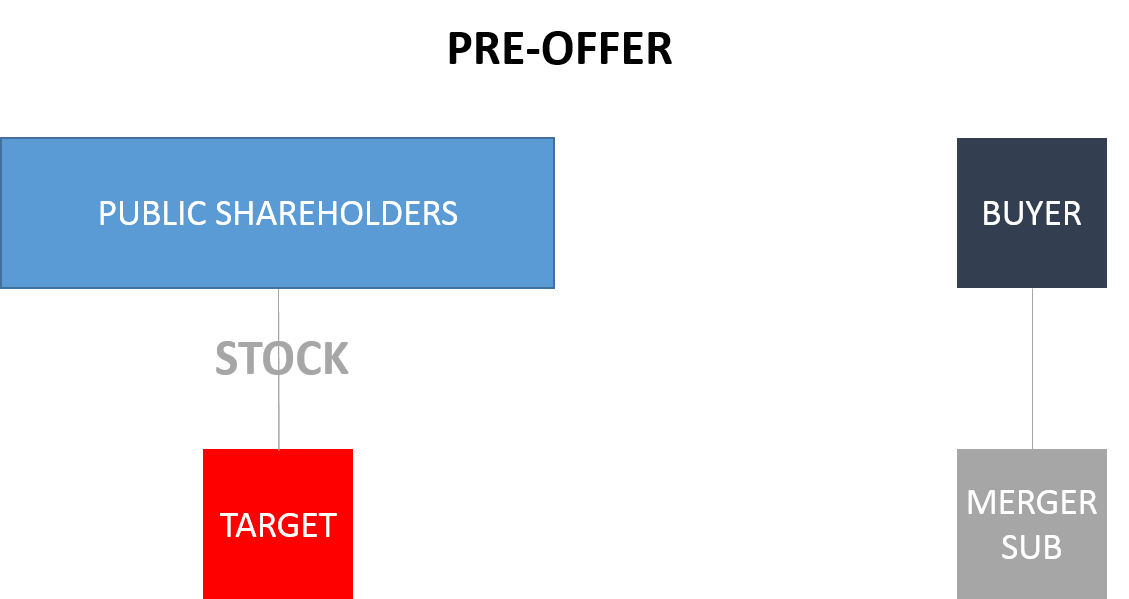

A merger is a combination of two different legal entities into one entity, where one of the entities survives and the other disappears. The surviving entity retains all ownership and other rights of both constituent entities. Merger transactions are effected pursuant to the law of the state(s) of formation of the entities being combined, such as §251 of the Delaware General Corporation Law. Unlike stock and asset sales, nothing is actually transferred by the seller to the buyer. Instead, the target company and its shareholders agree to permit the target company to be merged with the buyer or, more frequently, a newly-formed, non-operating subsidiary of the buyer. Usually, the target is the surviving entity in the merger, with the subsidiary of the buyer disappearing. This is commonly referred to as a reverse subsidiary merger. It is consummated by filing one or more certificates of merger or analogous documents with the secretaries of state of the constituent companies’ states of organization.

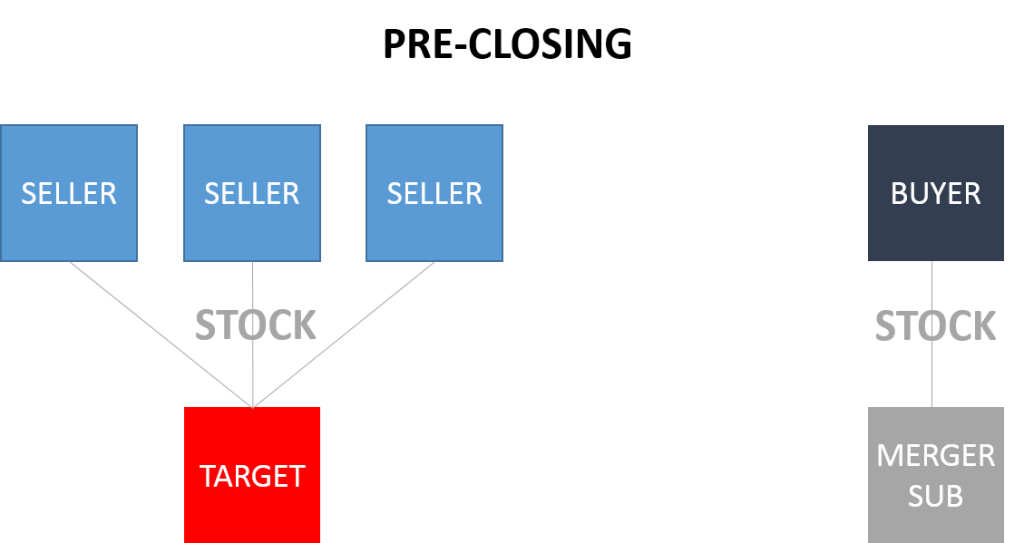

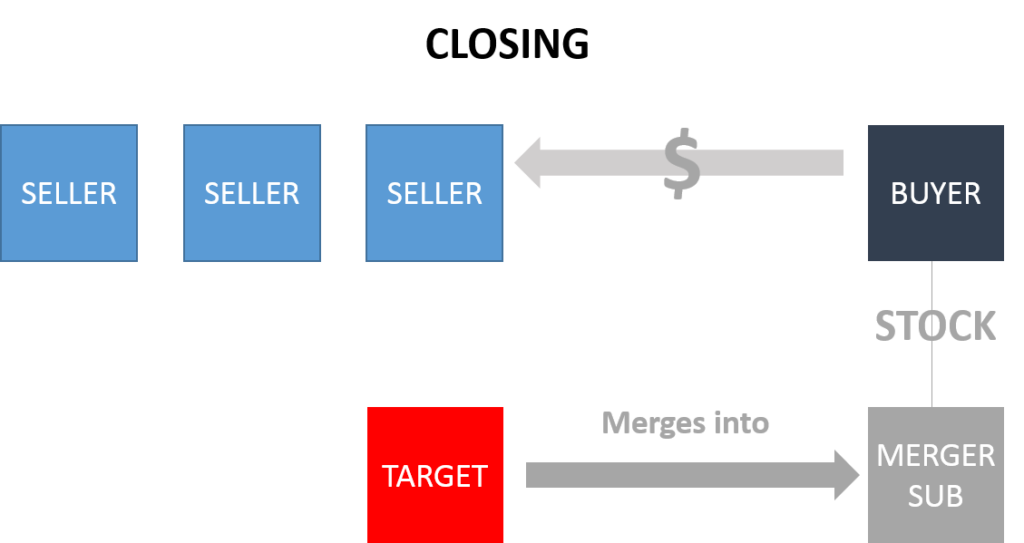

Here’s an illustration of the reverse subsidiary merger transaction structure:

The advantages and disadvantages of a merger structure include, among others:

- It enables the buyer to obtain ownership of 100% of the stock of the target company, even if less than all of the target company shareholders agree to the sale. Unless otherwise set forth in the target company’s organizational documents, most states only require holders of a simple majority of the target company’s equity securities to approve a merger.

- The buyer does not cherry pick the assets and liabilities it acquires, as it would in an asset deal. Unless they are specifically and affirmatively retained by the selling shareholders, all assets and liabilities are held by the surviving company in the merger.

- Aside from express indemnification obligations (or exceptions to the exclusive remedy provision of a merger agreement), selling stockholders do not retain any liabilities of the target company post-closing.

- Given the need to obtain shareholder approval, it may take longer to close a merger transaction than a stock purchase.

- As in a stock purchase transaction, it generally requires fewer third party consents and instruments of transfer than an asset sale.

- Because they can be effected with fewer than all target shareholders approving the transaction and do not present the challenges of an asset sale, mergers are the transaction structure of choice for public company transactions.

- Target company shareholders may have appraisal (dissenters’) rights, which entitle shareholders who do not vote in favor of the merger and otherwise adhere to specified requirements to petition a court to determine the value of their shares. Once determined, these dissenting shareholders would be entitled to receive that value in lieu of the merger consideration.

- The deal may be structured as a tax-free reorganization under §368 of the Internal Revenue Code if all or a substantial portion of the purchase price is paid with stock of the buyer.

- As in a stock purchase transaction, it is generally advantageous for a seller because of the benefit from capital gains tax rates. The purchase price minus the shareholders’ basis in the stock equals the recognized gain. This gain is considered a capital gain and is taxed at the capital gains tax rate, which is usually lower than the ordinary tax rate.

Structure No. 4 — Two-Step Merger / Tender Offer.

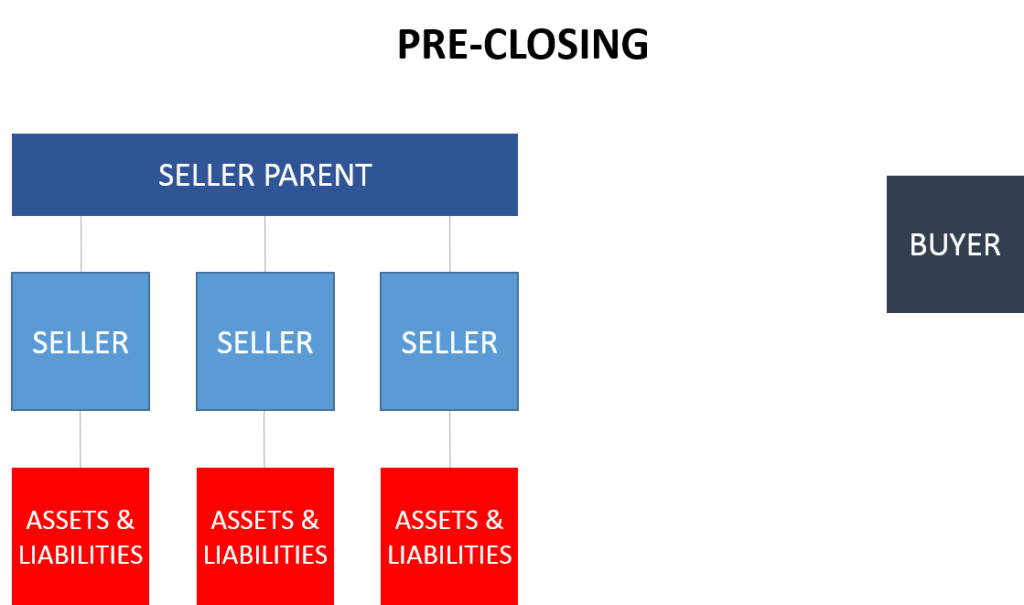

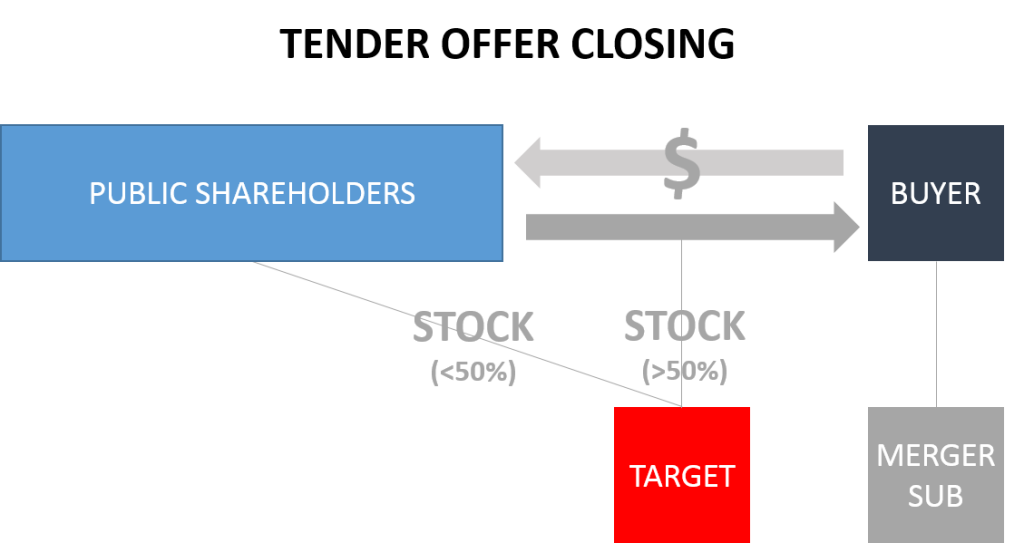

A target company may also be acquired via tender offer, an offer to purchase some or all of a corporation’s broadly-held stock directly from the company’s shareholders. This acquisition method is most frequently employed in the public M&A context, as it enables acquirers to make offers directly to a large number of target shareholders, even without the consent of the target company’s Board of Directors or management.

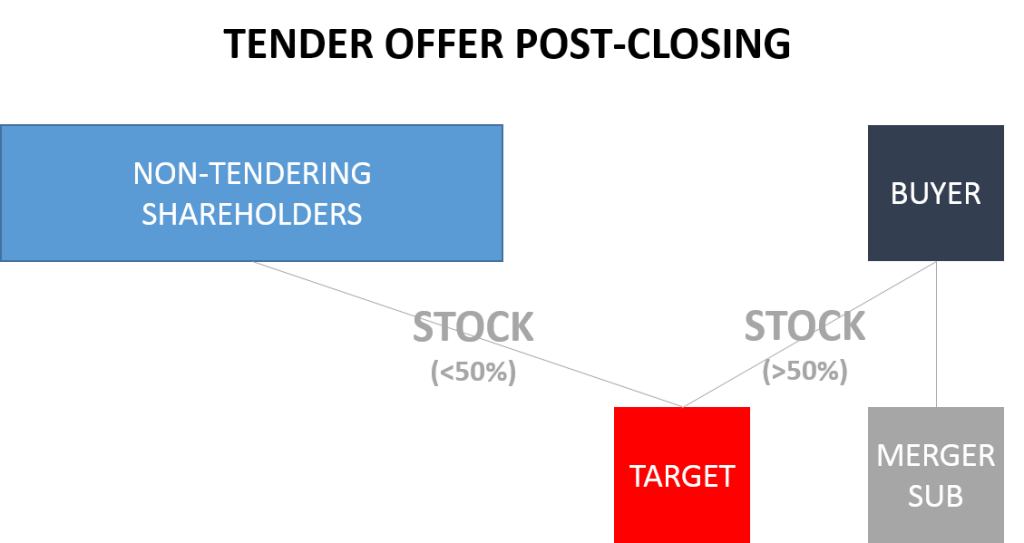

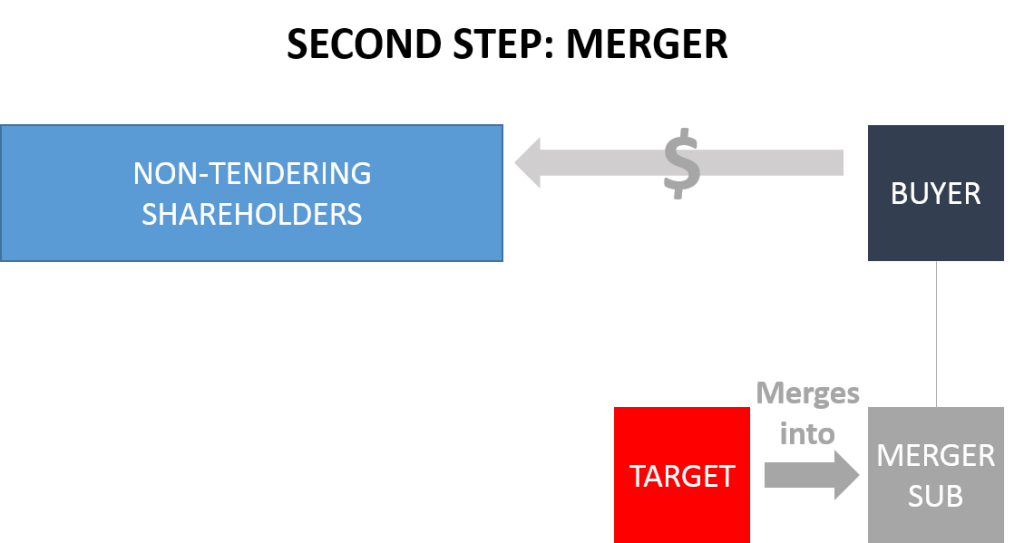

Because it is extremely unlikely that all target shareholders will tender their shares (other than in the private deal context, where it is a more plausible possibility), tender offers are generally employed as the first step in a two-step acquisition process, a so-called two-step merger. The second step involves a squeeze-out merger, through which, once the buyer has secured control over at least a majority of the target’s shares, it can cause the target to be merged with a wholly-owned subsidiary of the buyer.

Here’s an illustration of the two-step merger transaction structure:

The advantages and disadvantages of a two-step merger structure include, among others:

- It is similar in many respects to a negotiated merger. The primary difference is that a two-step merger may be conducted without the need to convene a shareholder meeting and obtain shareholder approval of the transaction. This means that, generally speaking, two-step transactions may usually be consummated more quickly than negotiated mergers in the public deal context.

- The two-step process is the only mechanism through which a buyer can acquire a target business without the consent of the target Board of Directors or management. Thus, virtually all hostile M&A transactions are structured as tender offers to be followed by squeeze-out mergers. Technically, a stock purchase transaction may be consummated without the cooperation of the target Board or management. However, in reality, in any circumstance where there is sufficiently concentrated ownership of a target company to be able to negotiate a sale of a control block of shares, the subject company’s Board and management will, by and large, be under the direction of the controlling shareholders.

- Like a negotiated merger, it enables the buyer to obtain ownership of 100% of the stock of the target company, even if less than all of the target company shareholders agree to the sale.

- Aside from express indemnification obligations (or exceptions to the exclusive remedy provision of a merger agreement), selling shareholders do not retain any liabilities of the target company post-closing. In public deals, selling shareholders do not retain any post-closing obligations whatsoever.

- As in a stock purchase or merger transaction, it generally requires fewer third party consents and instruments of transfer than an asset sale.

- While negotiated mergers have historically been a significantly more popular means of structuring public M&A deals. However, 2006 amendments to the all-holders, best-price rule (Exchange Act Rule 14d-10), which, prior to the amendments, had made it more difficult to offer certain retention and other rewards to target company management, have increased the popularity of the two-step merger approach. In addition, Delaware, which is the jurisdiction of incorporation for a majority of public companies, amended its rules in 2013 to permit acquirers to consummate a short-form merger without a stockholder vote by a buyer holding a simple majority of the voting rights, down from the 90% of the voting rights that were previously required.

- Target company shareholders may have appraisal (dissenters’) rights in connection with the squeeze-out transaction.

- The deal may be structured as a tax-free reorganization under §368 of the Internal Revenue Code if all or a substantial portion of the purchase price is paid with stock of the buyer.

* * *

Erik Lopez is the M&A lawyer responsible for this blog. Feel free to contact Erik at erik@jassolopez.com or +1-214-601-1887.

Erik Lopez

Partner at Jasso Lopez PLLC

Erik is an M&A lawyer with over 23 years of domestic and cross-border, public and private M&A experience. He has successfully closed hundreds of deals totaling tens of billions of dollars in value for a global client-base. He is a graduate of the University of Chicago and New York University School of Law. You can reach Erik at erik@jassolopez.com.